There are four major stages, with minor stages within each

A. Planning a ParEvo exercise

B. Implementation of a ParEvo exercise

C. Evaluation of the exercise content and process

D. Discussion of ParEvo contents and process and Evaluations thereof

A. Planning a ParEvo exercise

At its simplest, this should involve thinking through the choices to be made in stages 1 to 5 in implementation, as listed immediately below.

Ideally, any ParEvo exercise would also be preceded by an orientation workshop which involves all available participants, the facilitator(s) and other relevant parties e.g observers (see below). In that meeting the facilitators should describe the aims of the exercise, how it will proceed, the evaluation stage and any follow up activities e.g planning events making use of the exercise and its evaluation findings. Please also include explicit references to the Privacy Policy..Questions should be solicited from the participants and answered in full. The aim of this event should be, at a minimum, to secure informed consent of their participation, and preferably also much more i.e interest, enthusiasm and engagement in the whole process.

B. Implementation of a ParEvo exercise

1. Clarifying the aim of a ParEvo exercise

2. Identifying who will be involved

3. Describing the starting point of the process

4. Defining the time span

5. The facilitator provides guidance to participants

6. Participants make their contributions

7. Developing storylines are shared

8. Re-iteration of 5, 6, 7

9. Evaluation, within exercise

C. Evaluation, post-exercise

1. Using an online survey

2. Using downloadable data

D. Discussion of storylines and evaluation judgements

10. Using the products of the ParEvo process

11. Impact assessment

How much time will we need?

A. Implementation of a ParEvo exercise

Planning a ParEvo exercise is important. At almost every stage described below, there are design choices which can make a significant difference to how the exercise proceeds, and the value it provides to the participants.

1. Clarifying the aim of a ParEvo exercise

2022 02 20 Update: Exercise objectives can be defined in four areas:

- The process: How people participate

- The outputs: The contents of the storylines that are generated

- The outcomes of the exercise:

- Cognitive: Changes in how people think about the future (meta-cognition)

- Behavioral: Changes in how people plan to (or do) respond to the possible occurrence of events described in the storylines

1. Process objectives

These can be about how people participate. For example:

- Identifying future scenarios which have maximum ownership by all participants

- Identifying which participants are particularly good at making contributions valued by others, and vice versa

- Identifying which participants are most similar and most different in their perspectives on a given issue

- Doing research on what forms of participation are associated with the development of scenarios that are positively evaluated on criteria like probability and desirability, or the opposite

2. Content objectives

ParEvo can be used to develop alternative views of:

- What might happen in the future, or

- What has happened in the past

Alternative futures can be of two types:

- Forecasting, where there is no prior view of what the desired end state is, for any particular time in the future.

- Backcasting, where there is an agreed end state, which any scenarios being developed should lead to.

In practice the Facilitator will usually have more specific ideas on what kind of possible futures or past histories they are interested in. .These will be need to be expressed in the exercise title, the guidance given at the top of the parevo.org exercise page and in the seed paragraph

3. Outcome objectives

3.1 Cognitive changes

During and after a ParEvo exercise changes may take place in about how we think about the future. How we think about the future has been described by some as “futures literacy“. Alternatively, we can see this as a form of meta-cognition. Cognitive outcomes may be in the form of identified gaps in our imagination, questionable or critical assumptions, or contradictions. Facilitators of ParEvo exercises are likely to have their own particular view of what sorts of changes in thinking abut the future would be most desirable, and should try to make these explicit.

3.2 Behavioral changes

After a ParEvo exercise is completed, at various points in the future, participants may change their behavior in the light of reflections on that exercise. Facilitators should try to identify the kinds of behavior changes that would be of interest given the context of their exercise. One way of thinking about kinds of behavior is to think about what kinds of responses would best fit different kinds of storylines. Here is one framework that might be useful. Rows and column headings describe different combinations of storyline characteristics. Cell contents describe behaviors that might be appropriate for each of these 4 combinations.

| Storylines are | Undesirable | Desirable |

| Likely | Prevent beforehand, mitigate afterwards | Compare and harmonise with pre-existing plans |

| Unlikely | Monitor any possible changes in their status e.g becoming more likely | Enable beforehand, exploit afterwards |

Postscript: Developing Theories of Change

Most ParEvo exercises to date have asked participants to describe “possible” sequences of events, which may fall anywhere within a range of likely to unlikely, desirable to undesirable, as seen in Figure 1. However, the contents of a Theory of Change (ToC) would normally be all about expected (i.e hopefully likely) and desirable events. If the purpose of a ParEvo exercise is focused very much on helping to develop a ToC, rather than simply updating it (as in Figure 1), then the ambit of that exercise will need to change. The Facilitator’s guidance may need to ask participants to write about expected and desirable events, not just possible events. How will this work out in practice? I have yet to see a practical example.

2. Identifying who will be involved

People can be involved in one or more of 6 different roles:

- The ParEvo Administrator who approves requests from people to act as a Facilitator, and provides them with the parameters they can control. Ongoing technical support and advice can also be provided to Facilitators during the planning and implementation of an exercise.

- A Facilitator(s) who invites participants, sets up the framework within which they can participate, and provides continuing guidance throughout a ParEvo exercise.

- Participants (aka Contributors), who generate the contents of scenarios within a ParEvo exercise

- Commentators, who comment on the contributions made by participants. Commentators can be Contributors, and/or the Facilitator, and/or other parties.

- Evaluators, who evaluate the storylines at the end of a ParEvo exercise. They can be Contributors and/or Commentators

- Observers, who can view the contents generated by a ParEvo process, in real-time and after completion. But not to add content in any way. This is done by sharing an exercise-specific hypertext link.

Three roles are essential: The Administrator, a Facilitator and Participants, all others are optional

Participants can participate as individuals, representing their own views. Or they can represent their role in an organisation. Or they can represent the views of other stakeholders. Or, in each iteration, they can voice the views/behaviour of different actors who could be involved in the unfolding events. Or as individuals, participants can each represent a whole team or unit , within an organisation, voicing a particular interest or perspective. Approaches which maximise the diversity of views are likely to be helpful. But all within the constraint that participants should be expected to have a shared interest in the scenarios being developed.

The minimum number seems likely to be four, but larger numbers are preferable. Larger numbers will generate more diversity of views. For more on this question see “How many is too many” Diversity is what drives the ParEvo process. With really large numbers it may be best for these to be broken into a number of small teams, each acting as a quasi-individual. There is some evidence that diverse teams (each with more homogeneous members) may be the best way way to solve complex problems (Pescetelli, et al, 2020)

As mentioned above, all participants must initially be invited by a ParEvo exercise Facilitator. They then register as participants on the ParEvo website, to obtain a password. This then enables them to log onto the ParEvo website thereafter and gain access to any of the exercises they are involved in.

2020 03 26: There needs to be some degree of fit between the characteristics of the group of participants and the purpose of a ParEvo exercise. The purpose has to be motivational in one respect or another. Asking people to speculate on alternate futures that they either know little about or whose contents will have little consequences for them, may not be very productive.

3. Describing the starting point of the process

This is a seed paragraph of text, providing a common starting point for all subsequent contributions. This can be a real event or an imagined event. Think of it as the opening paragraph in the first chapter of a novel. The event will typically happen at a particular point in time, that is made quite clear. The seed paragraph will normally be drafted by the Facilitator.

4. Defining the time span

This has two dimensions: duration and granularity

Duration is the total length of time that a set of ParEvo generated storylines are expected to cover. At the planning stage, specifying the duration is probably desirable, but it is not necessary. Choices can be made during the exercise.

Granularity is the total length of time covered by a single iteration So far, this has varied from three months to a year. Shorter duration exercises tend to have more granularity i.e. cover shorter periods of time per iteration

The total number of iterations will be a function of the desired duration and granularity

The optimal number of iterations may depend partly on the number of participants. If the number of iterations equals the number of participants +1 then this means that each participant will have had the opportunity to build on the contributions of each of the other participants, at on at least one occasion. This might represent a minimal ideal level of opportunity to explore and exploit the diversity of ideas presented by the diversity of participants. In practice, in the exercises completed so far, only one of the exercises has extended this far.

A note on time: Each iteration can be introduced as a consecutive period of calendar time, a temporal framework within which all participants have to work within. Or, no time definition can be given for each iteration. The only requirement being that the events in the current iteration have to be events that took place after the previous iteration. Within this option each participant will be describing events in their own “subjective” time, which may move at different speeds within one iteration and the next, and it may move a a different pace to that of other participants. The main requirement here is that participants do continue to signal, one way of another, when the events they described, did happen.

5. The Facilitator provides guidance to participants

In each iteration, from the beginning onwards, the facilitator needs to provide participants with some guidance. This will be found at the top of the ParEvo user interface, as seen in this example. It can include the following:

- Minimal requirements for participants’ contributions:

- maximum length,

- plausibility/probability and consistency requirements. Most often participants are asked to describe “possible” events.

- deadlines for contributions

- guidance on civility, etc

- Context setting information.:

- Reminding participants of the overall purpose of the exercise

- (Optionally) providing information on “surrounding developments” that the emerging storylines might need to take into account.

- Privacy policy:

- A link to the Privacy Policy is essential: https://parevo.org/privacy/

6. Participants make their contributions

In this first iteration, all participants:

- Receive and read the guidance from the facilitator and then

- Contribute an additional section of text describing what they think might happen next. This action develops the beginning of N storylines, where N = the number of participants. It contributes “variation”, one of the three essential parts of the evolutionary algorithm

7. Developing storylines are displayed and shared

When participants log onto the ParEvo webpage and then access the particular exercise they are involved in they will see a view like the one below, with five different parts:

- The Facilitators guidance in the centre top area, with the exercise title above it

- A graphic representing the exercise theme, on the top left

- The seed text, underneath the Facilitators guidance.

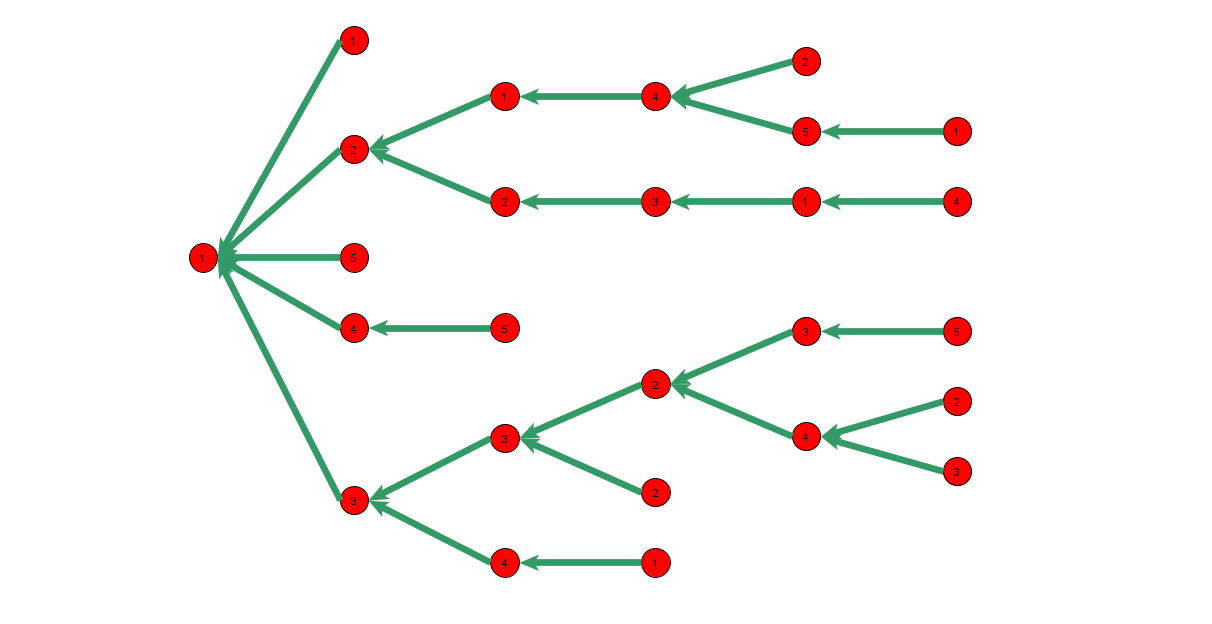

- A tree structure, on the left side, enabling participants to navigate along and between different storylines, while seeing how they connect to each other. This is supplemented by a scrollable column of text in the center of the page, representing the currently selected storyline of interest.

- Though not shown here, there is also a space for comments on contributions.

The identity of the contributor of each paragraph to each storyline is not made visible. The intention is that the participants’ focus should be on the content of the contributions, uninfluenced by knowledge of who the contributors are. Their identity will be known to the Facilitator (see more below).

Participants do not get to see each other’s contributions until all have contributed to a given iteration. At that point, these are all displayed at once, as above.

8. Re-iteration of 5,6,7

A new iteration only begins when all participants have contributed to the previous iteration, and they have been displayed.

Facilitator updates guidance to participants

This may or may not be needed at the beginning of each new iteration, depending on participants previous behavior and the need to introduce any new information about the imagined “surrounding context”

Participants add new contributions

At the beginning of each new iteration all participants are asked to look at each of the developing storylines and choose one which they would like to extend with a new contribution of their own. Each participant can only make one contribution, to one existing storyline, per iteration. But with each new iteration, they can change their mind about which storyline they now want to contribute to. As above, their text contribution could be a good, bad or neutral development, as seen from any stakeholder’s perspective. Participants can choose to add to any previous contribution, made by others or by themselves. As before, these contributions are anonymous.

What guidance should participants be given on how to choose which previous contributions to build on? Up to now the default response has been to provide no guidance but allow people to choose according to their own desires. But an argument could be made that the Facilitator should ask the participants to try and maximise the diversity of storylines when they are thinking about the content of their contributions. This would be consistent with the overall purpose of ParEvo which is to generate a diversity of alternative futures, and views on how these can be responded to.

Previously I had thought that fast iterations would be a good thing, making fewer time demands on participants and delivering results sooner than later. But a paper by Bernstein et al ( 2018) titled “How Intermittent Breaks in Interaction Improve Collective Intelligence.” suggests otherwise, that delays between iterations might be beneficial.

Display and sharing of contributions

After all participants have made their next contribution the display is updated to show the extended contents of each of the storylines. If more than one participant chooses to add their next contribution to the same existing storyline then that storyline now branches and becomes two (or more) storylines. On the other hand, if some existing storylines did not receive any new contributions they remain as viewable storylines but are now treated as “extinct”. These storylines can no longer be added to in subsequent iterations of participant contributions. The total number of storylines in an iteration will always equal the number of participants.

9. Evaluation, within an exercise

Evaluation of content

The progress and achievements of a ParEvo exercise can be assessed in three ways:

1. Participants Comments

Participants can be enabled to post Comments the contributions that have been made. The use of the Comment facility is optional. The Facilitator decides if and when to allow Comments and individual participants can choose if and when to make comments during any given iteration. They can make a maximum of one comment per storyline in a given iteration. This comment facility can be used as the second part of each iteration of the ParEvo process. But only after all new contributions are received and displayed in a given iteration. These contributions are anonymised and all displayed at once, prior to the commencement of the next iteration.

2. Participants evaluations – within ParEvo

At the end of the ParEvo process, the facilitator triggers an evaluation stage, where participants are asked to rate the surviving storylines, on two default criteria: (a) their probability of happening in real life, (b) and their desirability of happening, or any other relevant criteria. See Figure 3 below.

The Facilitator can edit and change the default evaluation criteria. Other criteria, such as novelty, or observability, may be more useful in some circumstances. (See Pugh, 2016)

After all responses have been received the aggregated responses of all participants to the built-in evaluation questions are shared with all participants, through a display as seen in Figure 4 below. The ratings of each storyline can be viewed by clicking on the right and arrows above the evaluation panel.

B. Evaluation – post exercise

Using online surveys

Survey Monkey (or similar) can be used to ask participants additional and more open-ended evaluation questions. See the design and results of such a survey associated Alternate futures for the USA 2020+ exercise. The following types of questions can be asked:

- Questions about specific storylines

- Closed ended questions, like those above about desirability and probability

- Open ended questions, such as the “most significant difference between the storylines”

- Questions abut the whole set of storylines

- What was most surprising about the content, or what was absent from the content

- How much the events were likely to affect the participant, and how much the participant could affect the events

- Questions about participant’s judgements versus that of others

- How optimistic their own contributions were, versus those of their own

Postscript: 2021 07 28: There is a now a dedicated web page here on this site with a growing menu of different types of evaluation questions.

You can also see an example of an external survey used in association with the Alternate futures for the USA 2020+ exercise

Using downloadable data

At the end of a ParEvo exercise, the following kinds of data can be downloaded in an Excel file format, and subject to further analysis:

C. Discussion of storylines and evaluation judgements

10. Using the products of the ParEvo process

Caveats:

- This part of the ParEvo workflow is not expected to happen online, within the ParEvo app. It could take place in face to face meetings or via video conference calls

- The list of steps below is provisional and is very likely to be revised in the light of experience gained from new ParEvo exercises.

1. Identifying the kinds of storylines that are missing

Examine the scatterplot: When a set of surviving storylines have been located in a scatterplot, with axes such as likelihood and desirability, some attention should be given to the nature of that distribution. Are there some conspicuously empty spaces in the scatterplot, where there is an absence of storylines describing what might be happening there? If so, this may have implications for the design of any subsequent ParEvo type exercises. The assumption here is that a diversity of storylines i.e. occupying a whole range of possible types, is desirable, because it will mean the people or organisations involved in an exercise will have to think more widely and flexibly about their possible responses.

Use the Search facility: : As the number of iterations increased the proportion of storylines that have not survived will increase, and soon exceed the number of surviving storylines. These need attention, because they represent gaps, i.e. potential themes and directions that have deliberately ignored. Key word searches can be used to test ideas about what is being neglected i.e. is more common in extinct storylines. For example :

2. Identifying major disagreements about the storylines

When participants are asked to identify the most likely and least likely storylines, it is not unusual that there will be some disagreement in these judgements. For example five people might rate a particular storyline as most likely, and one other might rate it as least likely. Where outright contradictions of this kind occur these need to be resolved before there can be any coherent thinking about an appropriate response to a particular storyline. This is most likely to involve discussion between participants, and perhaps other parties.

Resolution: There are two possible outcomes of these discussions. Firstly, agreement will be reached about the likelihood of the storyline happening, in which case discussion can proceed about how to best respond to the possibility ( see more on this in points 3 & 4 below). The second possibility is that no agreement can be reached about likelihood, so storylines in this category can be characterised as having what is called “Knightian uncertainty“

Hedging: For scenarios characterised by Knightian uncertainty responses need to be generalised and robust. That is, they should be widely applicable across different circumstances, even though this may be at the cost of being the optimal response in a particular situation. For example, when a company is concerned about the uncertainty of its future it might decide to increase its capital reserves. Even though this will be at the cost of efficiency in the use of capital i.e it will not be an optimal response. In the social and biological world these strategies are sometimes called “bet hedging” strategies. For more, see this Wikipedia article on bet-hedging in biology.

Randomisation of choices can also be an option, where a menu of available choices can be identified. For more on this (seriously proposed) option see “On the usefulness of deliberate (but bounded) randomness in decision making”

3. Prioritising analysis of specific kinds of storylines

When a set of surviving storylines has been plotted on a likelihood x desirability scatterplot there will be four broad categories of storylines that can be prioritised for more detailed discussion. This is my suggested priority order, which would probably bets be checked with the participants in any ParEvo exercise. :

- Least desirable but more likely storylines

- More desirable but less likely storylines

- More desirable and more likely storylines

- Less desirable and less likely storylines

4. Responding to specific storylines

Within each of these categories different types of responses would seem to be appropriate:

- With storylines which are least desirable but more likely the concern here will be with risk,

- and how it could proactively be inhibited or retroactively be mitigated.

- With storylines which are more desirable but less likely the concern here will be with opportunity,

- and how it could proactively be enabled or retroactively capitalised

- With storylines which are more desirable and more likely, perhaps the focus will be on checking against, and updating, any prior strategies about where the organisation wanted to go.

- With storylines which are least desirable and least likely, the most appropriate response may be to periodically revisit, and if necessary, update this assessments about likelihood.

5. Identify responses that will work across multiple storylines

A suggestion borrowed from Scoblic (2020): For example isolation and tracing are two strategies that are appropriate across many different kinds of epidemics and pandemics. These events (as described by different storylines) may be undesirable but vary in probability, or be desirable and vary in probability..

This option is similar to that proposed for Knightian uncertainty type storylines, but if it is focused on storylines with relatively known likelihoods it could be more customised and efficient in resource use.

11. Impact assessment

Caveat: It is likely that ParEvo platform will be used for different purposes, so the approach to impact assessment outlined below may not always be relevant.

Assumptions re ParEvo exercise objectives

The design of the ParEvo process has at least three hypotheses/assumptions built into its design:

- A ParEvo exercise will generate a range of alternate futures, beyond those previously considered by each individual on their own

- Participants’ reflections on possible responses to different kinds of storylines (via section 10 above) will be enable participants to have greater adaptive capacity in the face of future uncertainties. This will be evident at two levels:

- Cognitive:

- Participants will be able to identify the strengths and weaknesses in how they have imagined alternative futures

- Participants will be able to identify a range of possible and relevant responses to different storylines they have imagined

- Behavioral: Participants actual behavior will change, as they implement some of these possibilities

- Cognitive:

- The balance of these two processes (1 and 2) will affect participants’ sense of agency in a positive way. That is, a greater sense of being able to influence future events relative to being influenced by them. This is of consequence because in the worst case e.g with the more dramatic climate change scenarios, the sense of agency in the face of massive environmental change may be destroyed and lead to despair and inaction.

Questions need to be designed around each of these objectives

Assumptions 1 and 2 could be investigated by asking participants about what kinds of new scenarios, and new possible responses to those scenario’s, they had recognised as they participated in a ParEvo exercise. And what kind of follow up actions they had taken, i.e. in implementing any of those responses.

Assumption 3 might be investigated by asking two rating scale type questions, which have already been trailed in a previous ParEvo exercise. The first question asks “To what extent do you think any of the events described in any of the storylines are likely to affect your life in the next two years?“, using a response scale ranging from “Not at all”, through “Neither/Hard to Say” to “A lot”. The second question asks “To what extent do you think you will be able to have an effect on any of the events described in the storylines? “, using the same type of scale.

Figure 4 shows 12 participants responses to these two questions from a 2021 ParEvo exercise about COP26 and climate change. Blue nodes = participants. The average difference between each participants two ratings was -23. i.e. their expectation of being influenced was greater than their expectation of being able to influence. Perhaps not so surprising. However, looking at the scatter plot there was some clustering. On the top left were those who mainly felt influence, whereas those in the top right had a more balanced view or being both influenced and influencing. On the bottom was one respondent outlier, who felt more able to influence than any others. All the judgements would probably benefit from further inquiry.

Given the expectation of participants experiencing “...a greater sense of being able to influence future events relative to being influenced by them“, how good is the relative sense of agency in Figure 6? What is still missing is a relevant comparator. It may be feasible to ask the same two questions prior to the beginning of a ParEvo exercise, where participants current views of the future, and its likely impact and influenceability, are the baseline.

How much time will we need?

(this section is incomplete)

- Planning

- By Facilitator: Possibly 2-3 person days, spread over a number of days/weeks:

- Implementation

- By participants:

- Attending introductory briefing meeting online (optional) = 1 hour

- Reading existing contributions and writing their own new contribution: 35 minutes per iteration

- By Facilitator

- 1 hour for introductory briefing for all participants (optional)

- 30 mins per day, to notify participants of each new iteration and to remind people to contribute on time

- 1 hour per iteration to do ongoing content analysis coding

- By participants:

- Evaluation

- By participants:

- 30 minutes for a single online survey (essential)

- 1+ hour for an online group discussion (optional)

- By Facilitator

- 0.5 days for design and testing of online survey

- 0.5 days to invite and remind participants of survey

- 1 day to collate and review survey findings

- By participants:

- Analysis

- By Facilitator and others