Purpose

The purpose of this webpage is to document the process that was used to design, manage and evaluate the fourth ParEvo exercise, known as 2020. Participants, and others, have added their views on the process. Please feel free to add any comments or questions below.

The reporting on the process is structured around the 12 stages outlined on the “How an exercise works” page of this website, which describes how to go about planning and implementing and evaluating a ParEvo exercise.

1. Clarifying the aim of a ParEvo exercise

The purpose of this ParEvo exercise was to give a wide range of people an opportunity to see how ParEvo worked. If the exercise works as well as intended I hope a number of the participants will then look for opportunities where they can use ParEvo in their own area of work, with themselves playing the role of facilitator rather than myself.

With this aim in mind, I had to find a topic that was likely to be of interest to a wide range of people. Climate change seemed to be an ideal topic.

As explained on the start here page, there are two possible types of purposes. One is a content objective, in this case, it’s to learn about different perspectives on what might happen to global warming from the year 2020 onwards. The other is a process objective. In this case, it’s to observe how people participate in the construction of these different storylines about climate change and to show participants how they can analyse this kind of data when they themselves are facilitators of a ParEvo exercise.

The “How an exercise works” page also makes a distinction between forecasting and backcasting. In this exercise we are doing forecasting because we have no particular end goal in mind, it’s an exploration of possibilities and we don’t know exactly where that exploration will take us.

Lesson 1: Give a ParEvo exercise that will grab people’s attention. “2020” was not ideal. Perhaps “Climate Change 2020” or something like this might have been better.

2. Identifying who will be involved

By 24 August 2019, there were 15 people who volunteered to be participants, from 12 countries (Africa 4, Europe 3, Oceania 2 Asia 1, North America 1). Two-thirds were men. These volunteers were recruited from the membership of the MandE NEWS email list. Of the 12 volunteers, 11 participated in the first iteration. This number dropped down to 7 in the fifth iteration. Six people took part in the evaluation of the seven surviving storylines.

Query 1: Is there a case for offering incentives for people to keep participating once they join in exercise? Perhaps a donation by the facilitator to a particular relevant charity or one identified by the participants themselves?

Query 2: With some exercises is there an argument for allowing open-ended participation in some form? For example, in the first iteration allowing the first 10 participants who sign up to make a contribution at that point. Then in the second iteration to allow the next 10 people to make a contribution, building on the results of the first iteration. Then in the third iteration to allow the next 10 people to do the same in turn, et cetera, et cetera. Or variations on this theme, such as automatically replacing any dropouts with new participants from a waiting list.

3. Describing the starting point of the process

The starting point of a ParEvo process is the development of a seed paragraph of text, which becomes the basis of all storylines which are developed by participants thereafter. All the participants will see this seed text as soon the ParEvo process begins and they are invited to make their first contribution, to be added to that seed text. This is the text that was used:

Early in the year 2020 global carbon dioxide concentrations exceeded 415 ppm for the first time in 900,000 years. July 2020 was the hottest on record, globally. These are some stories of what happened that year and thereafter. They tell us about some of the things that happened to the Earth’s climate locally and globally and how some people reacted and responded to those changes: both what they thought was happening and what they thought might happen next.

4. Defining the endpoint

Because this was a forecasting exercise, rather than a backcasting exercise, there was no endpoint which the storylines need to be orientated towards.

But another kind of endpoint was been defined and that is the number of iterations that this exercise will go through. It was planned to go through at least 10 iterations. In each iteration, the participants will have the opportunity to review the developing storylines up to that point and to decide which of those storylines they want to add a new bit of text extending that storyline.

In practice, only 5 iterations were completed because each iteration was taking longer than expected and participant numbers were falling as the exercise proceeded.

Query 3: Should participants be told the planned number of iterations and be asked to commit to participating in all of these?

5. The facilitator provides guidance to participants

At the top of the ParEvo webpage for any given exercise there is a short body of text written by the facilitator. That text provides guidance to the participants about their contributions. In this exercise that guidance was tweaked from iteration to iteration.

While carrying out this exercise I came across at least two items on the Internet which could provide some inspiration to the participants, stimulating their imagination about what could happen and how people react to climate change. I’ve listed these below. In future ParEvo exercises, it may be worthwhile if the facilitator identified in advance similar sources that could provide inspiration and context for the participants thinking.

- “Hello From the Year 2050. We Avoided the Worst of Climate Change — But Everything Is Different” by Bill McKibben, in Time magazine

- Act now and avert a climate crisis. Nature joins more than 250 media outlets in Covering Climate Now, a unique collaboration to focus attention on the need for urgent action.

During this exercise, there was no capacity to display a graphic image next to the Facilitators guidance text. This is now possible and should be used to help set the ambient mood within for an exercise.

6. Participants make their contributions

Because participants were located on multiple continents allowance had to be made for time zone differences when thinking about when they could participate. Initially, two days were allowed per iteration. In practice, most iterations 4 days or more between the first and last continuation was received. Bear in mind that all participants were volunteering their time.

Participants’ contributions in the first iteration varied in the span of time that their narrative covered. Facilitators needed to remind participants that there are 10 iterations and so they need to “pace themselves” i.e. not compress too big a span of time into the first few contributions.

Query 4: The facilitator may want to define each iteration as covering a specific span of time, rather than an undefined period of time.

The content of the contributions ranged from very focused on individual people to high-level descriptions about social trends. In response to the latter, the Facilitators guidance in iteration 2 onwards suggested that contributions would ideally refer to specific countries, organisations, people, times and places. Though some physical events might not necessarily involve people.

Query 5: To what extent should encouragement be given to developing specific types of storylines, versus just let whatever is there evolve in whatever direction is preferred? Was the guidance given in iteration 2 too prescriptive?

7. Developing storylines are shared

In each iteration, there are two phases. The first is a contribution phase where people add text to a selected storyline that they want to continue. The second is a comment phase, where people can comment or question the contents of those contributions. This is like a conversation about the conversation, a meta-level of discussion. Up to now, people have just been invited to comment as they wish.

Query 6: A more prescriptive alternative would be to only allow participants to comment on their own contribution, albeit anonymously. In those comments, they could elaborate on the thinking behind their contribution and why they decided to add to a particular storyline rather than another storyline.

8. Re-iteration of stages 5, 6, 7

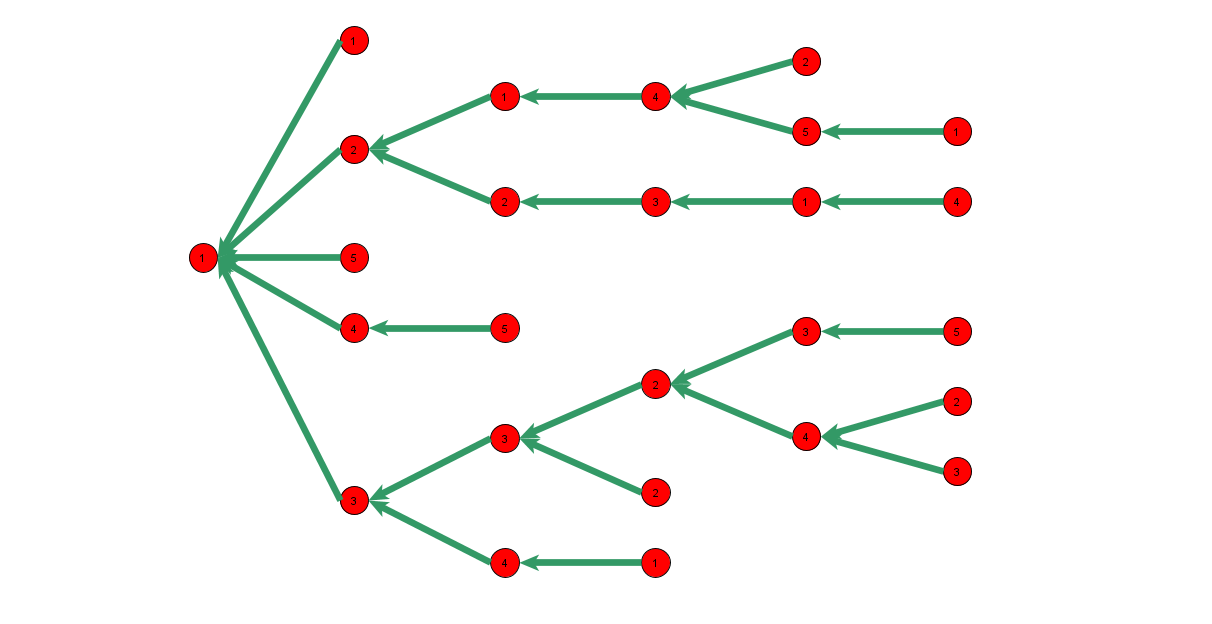

The seven surviving storylines, eleven extinct storylines and the accumulated contributions (42) making up these storylines can be seen here: https://parevo.org/exercise/2020 [Username: Guest. I will provide a Guest password here shortly]

9. Evaluation

Six participants took part in the evaluation stage. Their aggregate judgments on the seven surviving storylines were as follows:

These were more interpretable when plotted on a graph, as follows:

To read about the interpretation of this data see the Content Analysis

10. Follow-up

Other information…

“Hello From the Year 2050. We Avoided the Worst of Climate Change — But Everything Is Different“ by Bill McKibben, in Time magazine

1st interaction – some stories jumped quickly to solutions or a solution and perhaps left little room to expand (unless the storyline path was changed). Many early ones focussed highlighting the years of inaction (rightly so) but may be trapped in that – however, this does leave room for stories to expand over time. Many focus on reducing greenhouse gases – what about adaptions if we assume the greenhouse tipping point was reached or exceeded. Perhaps some scientific knowledge on what the initial scenario meant in terms of that may help focus scenarios

A number of other types of scenario planning approaches do make use of the expert opinion at the initial stages. But my preference with the ParEvo approach is to allow a range of people to develop alternative storylines based on whatever knowledge they have at hand. Then later on one could invite experts to look at the storylines and identify where the strengths and weaknesses are in people’s knowledge and expectations, and then perhaps provide that feedback to the participants. Scientific knowledge is important but understanding the range of public knowledge is also important.

I really like this approach – and the interface is easy to use. I have been trying to use the MSC technique to use stories to evaluate success in programmes but I think this will make it a lot easier. One thing that became clear is that people are not used to tell stories in a professional setting (something I found in my research as well). We all tell stories all the time, we just often don’t know where to start when someone asks us to tell a story – especially if it’s on such a complex topic in a professional setting. That is why I used a fairytale story spine to pretty great success (see ERSS Special Issue 37, Rotmann, 2017) in my behaviour change research. It provides prompts that help set the scene and frame the different elements of the “hero’s journey” and puts participants into a “storytelling frame of mind”. I hope we can collaborate on seeing how the two approaches would work together, Rick. I think they would complement and improve on each other. Sea

Thanks, Sea. I am interested in exploring many different ways of using ParEvo, including your approach mentioned above. Rick